The Art Market and the Environment : Can digital art be green?

[03/06/2022]The art world is belatedly but resolutely assuming its responsibilities with respect to the natural world. This is the last article in our three-part series on the ecological issues facing the art market and how the secondary art market can adopt a more environmentally friendly approach. Our first article focused on initiatives implemented by the art world, the second highlighted artists committed to environmental issues in some form or another, and our third looks at the environmental impact of a digital art market!

“Quite apart from the social implications, we know that all things digital have an impact on the climate and on resources; but this impact can be limited if Green IT rules are applied to the choice of software and servers”… Alice Audouin

Chris Precht, Isolation. The architect abandoned plans to sell NFTs due to the environmental impact of digital tokens.

In 2020-2021, the covid pandemic triggered a sudden interruption of gatherings of all kinds. In response, art fairs, museums and galleries moved quickly to set up online visits and viewing rooms to allow ‘visitors’ the opportunity to discover their artworks remotely. Faced with restrictions and empty auction rooms, the auction houses made immediate use of their online exposures with more or less success depending on their size, how developed their online clientele was before the pandemic and their geographical location. Websites were rapidly developed and updated, becoming far more effective in offering virtual exhibitions in 3D, posting numerous interviews and conferences and developing ultra-high definition images allowing the inspection of artworks down to the smallest details. This movement greatly improved the online shopping experience for the customers of auction houses and it represented a huge leap forward into a future that had very ostensibly already begun.

The challenge of all-digital

Artprice’s 2020 Global Art Market Annual Report was very clear in its observation that online is the new normal. Prior to covid, many buyers were already accustomed to online bidding, but the number of connections exploded as of the first lockdown, with a broader, younger audience and a clear influx of new customers. Thanks to digital technology, many auction houses started to abandon their traditional summer break and maintain a sales activity all year round. In 2021, no less than 121,000 fine art lots were sold in the third quarter of the year. But while lockdowns certainly reduced greenhouse gas emissions, the switch to digital is not without impact on the planet. The more a digital activity uses a large amount of data, the more energy it uses. Even if the CO2 emissions generated by art e-commerce are lower than those generated by physical auction rooms, the digital activity has an ecological footprint and the different players in this business – from the artists to the auctioneers to the collectors – are all becoming increasingly aware of this reality.

In a statement by Art of Change, Alice Audouin recalls that the carbon impact of the digital world will represent an estimated 9% of greenhouse gas emissions in 2025. Faced with this reality, certain market players are publicizing their strategies to address these issues. These include selecting web hosts powered by renewable energies, using greener search engines and messaging services, switching to dark backgrounds on web pages to save energy, using free software, etc. In his film Coronation, AI Weiwei used existing images thereby lightening the digital weight of his film and limiting the consumption of energy. Indeed, there are numerous ways to limit the digital impact on the environment and many of these initiatives are accessible to most people. Meanwhile, as we indicated in our previous article, ‘environmental commitment’ has become a real factor in the choices made by potential buyers, especially among the younger generations who are ‘native’ to the digital sphere and are highly conscious of societal and environmental issues.

The digitization of the art market is therefore already a challenge in itself. With the irruption of NFTs in our digital lives, programs designed to enhance the sustainability of practices must be further strengthened and their application accelerated.

The NFT revolution in green?

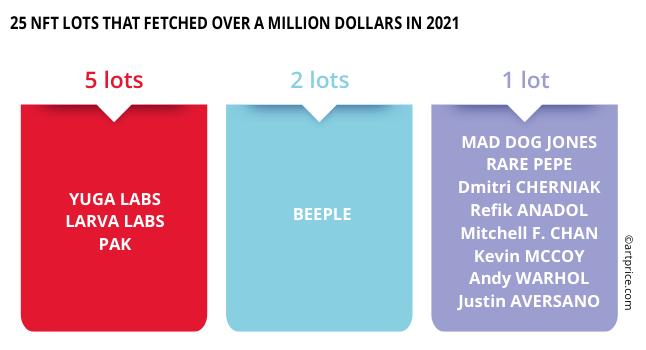

In 2021, the term “NFT” was elected by the Collins English Dictionary as “word of the year”, proving the popularity of the new phenomenon. It was a year that saw the sudden arrival in the art market of complete outsiders – but with high profiles in the crypto sphere – who were propelled into the world’s Top 500 most successful artists by auction turnover: BEEPLE ($98.5 million) took 19th place ahead of René MAGRITTE, followed by LARVA LABS (51st place) and PAK (113th place ahead of Henri MATISSE).

As digital art in the form of NFTs enjoyed an explosive entry into the art market – becoming one of the most discussed topics in the art world – it also raised some questions about its environmental cost. The creation of each NFT involves a number of transactions, and it has been suggested that publishing 100 crypto works generates more than 10 tonnes of CO2, more than the annual carbon footprint of a person living in the European Union. And, as we know, beyond the NFTs that have sold for astronomical sums in auction rooms or on specialized platforms such as OpenSea, thousands of non-fungible tokens are produced every day. Storing an NFT is not energy-intensive in itself, but the conditions of its creation and its transfer are. An environmentally conscious NFT buyer needs to understand the differences between blockchains so that he/she can identify the most sustainable networks.

At the heart of the Blockchain

Bitcoin, Ethereum, Monero or even ZCash… these are some of the best-known crypto-currencies among the thousands that exist. Most NFTs use the Ethereum blockchain to certify ownership of an asset. When a person buys an NFT, he/she sends the amount in Ether to the marketplace to initiate the transaction. The request is broadcast to the network of data miners and processed and validated in the form of complex mathematical cryptographics. Currently, most blockchains use the “PoW” (Proof of Work) protocol: several miners collect these “mathematical problems” and try to solve them. The first to succeed shows the result of their work (PoW) and receives a reward in cryptocurrency. Since only one miner will be rewarded for a block of sealed transactions, all the other computers also trying to get the reward will have worked for nothing. They will all have consumed energy but in reality, only one computer will have solved the equation to secure the transaction. The crypto solution is added to the next block, creating a blockchain that serves as a public ledger of all transactions. Once a transaction is added to this chain, it cannot be reversed or modified.

Originally, a relatively simple computer was enough to solve these equations. Part of the environmental impact of this phenomenon is a consequence of the incredibly rapid value accretion of cryptocurrencies. As the complexity of mining calculations increases with the number of machines trying to solve them, computers must now be incredibly powerful to absorb – and be the first to solve – the calculations. However, logically, the more powerful a computer is, the more electricity it consumes. Knowing that the biggest miners have mining farms of hundreds of machines – which essentially draw their power from fossil fuels – and that the very production of such devices is not exactly exemplary in terms of environmental protection, NFTs have a bad ecological reputation. Sustainability is therefore increasingly becoming a central criterion for the future of the blockchain industry.

Green mining: the solutions

An obvious first response in the attenuation of carbon emissions generated by the cryptocurrency industry is to make a transition to renewable energies. In 2021, less than 40% of bitcoins verified by PoW were mined using renewable energy. This is why lots of startups have emerged offering different alternative solutions. One aim is to optimize the profitability of mining farms by setting them up in geographical areas where the supply of electricity is greater than demand (the United States or Kazakhstan for example, but not in China, where the government banned mining activities on its territory in October 2021). Increasingly, with the rise in the price of fossil fuels, these companies are turning to renewable energies from hydroelectric plants in Canada, or geothermal plants in Iceland and El Salvador. Since energy storage solutions are not optimal and very expensive for technical reasons, the arrival of these industries represents a financial windfall as well as a means of selling production that would otherwise have been lost. The application of State-run carbon credits for cryptocurrency mining companies could also prompt them to buy carbon credits from other companies, thereby helping to offset the amount of emissions created around the world, or to switch to a greener energy to sell their own credits.

Emerging green cryptocurrencies rely on new protocols that reduce the carbon footprint of the blockchain technology. This is the case of Ethereum2, which plans to reduce its energy consumption by 99.95% by relying on the Proof-of-Stake (PoS) protocol, a system already used by other cryptocurrencies specifically oriented towards NFTs and blockchains, such as Algorand, Cardano and Solana. Under this framework, miners advance a small amount of cryptocurrency to gain access to an exchange for trades assigned to them. This reduces the risk of them approving fraudulent transactions, while eliminating the competitive computing element of the proof-of-work system, allowing each machine to work on a different problem and optimizing the energy consumed. Tezos, the rising blockchain for NFTs, has turned to “Delegated Proof of Stake” (DpoS) where users delegate their currencies to validators.

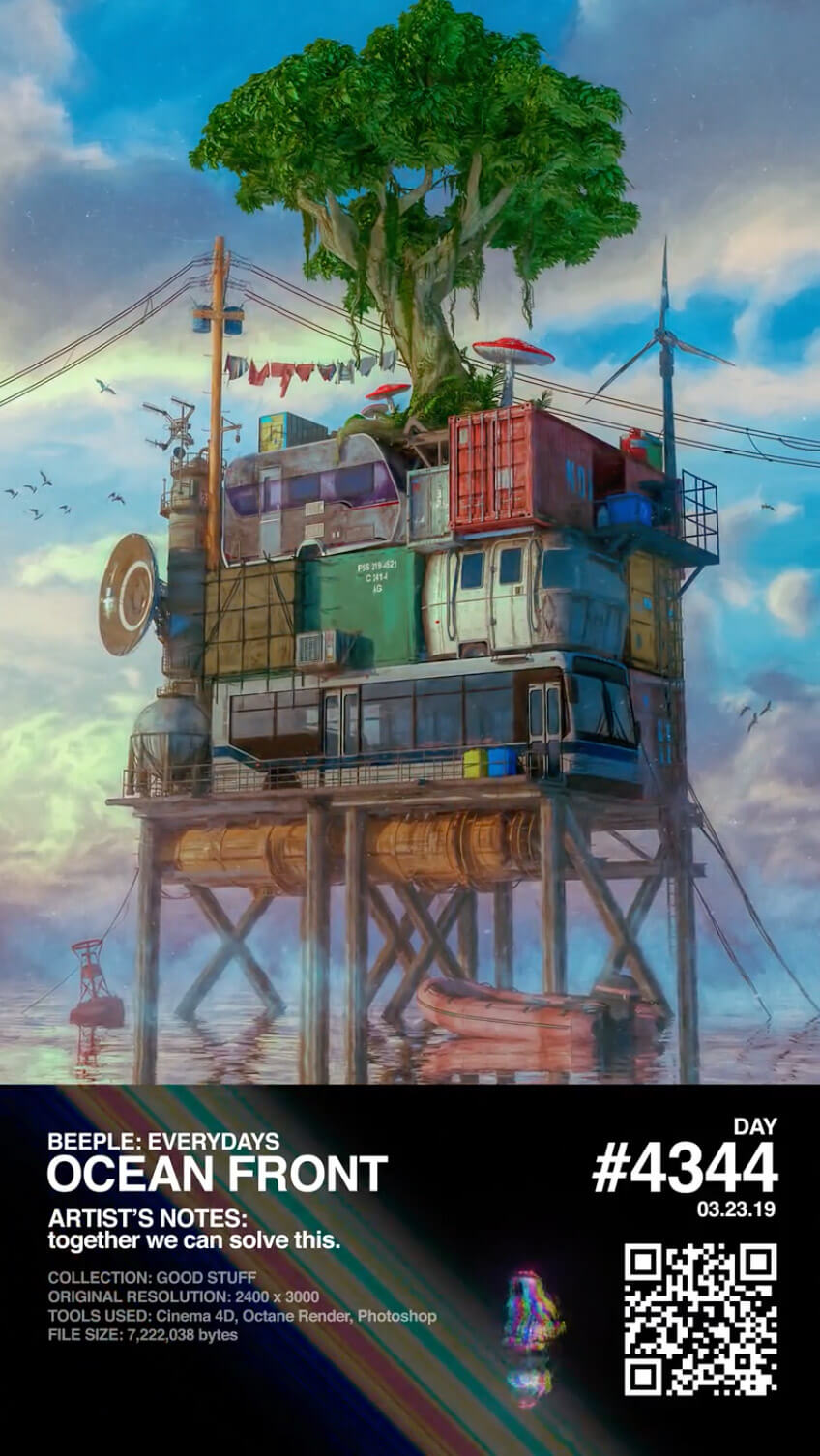

Beeple, Ocean Front

In any case, it is now clear that the main players in the world of NFTs have taken on the challenge of publicizing the sector’s efforts to become greener, sometimes at the cost of certain somewhat ironic contradictions. In March 2021, the NFT charity auction #CarbonDrop was held on the NiftyGateway platform. Eight artists including FVCKRENDER, Beeple, GMUNK, Sara LUDY and Refik ANADOL had donated their works. Crypto-entrepreneur Justin Sun happily paid $6 million, alone, to buy Beeple’s Ocean Front. The $6.6 million was used to fund Open Earth Foundation, a US non-profit organization, which aims to develop tools to transparently track global progress on the Paris Agreement. The event had a clear paradox: supporting climate change research while being supported by NiftyGateway’s Ethereum-based platform. To offset this, CarbonDrop innovated by attaching carbon credit NFTs to art NFTs.

In short, the crypto-art industry has been confronting the challenges of a more sustainable and more environmentally-friendly commerce for a several years now. Today, however, it can no longer avoid taking a number radical decisions and actions in order to comply with what artists and collectors now expect from them. It is within this context that industry professionals want to develop a global agreement to reduce the carbon footprint of cryptocurrencies. The Crypto Climate Accord is likely to set very ambitious goals: a transition to renewable energy by 2030 for all blockchains and a net carbon footprint reduced to 0 by 2040. So far, more than 200 companies, blockchains and individuals associated with the crypto, energy and technology sectors have joined the Crypto Climate Accord. The upcoming climate change conference (COP27) is expected to make sustainable art e-commerce solutions a key resolution.

0

0