Germaine Richier: major retrospective

[28/03/2023]Richier was the first female sculptor exhibited at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris in 1956. Nearly 70 years later, the Center Pompidou in Paris is – at last – hosting an unmissable retrospective of her work, bringing together 200 works.

Born in 1904 in France’s Provence region, Germaine RICHIER was not predestined to become an artist. As a child she discovered her natural surroundings, playing with insects in the mediterranean scrubland. Aged 12, she was highly impressed by the Romanesque statues of the Saint-Trophime cloister in Arles, and it was this encounter with sacred statues that ignited her interest in sculpture. In 1920, she started studying sculpture in the studio of Louis Jacques Guigues, a former Rodin practitioner, at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montpellier. She subsequently moved to Paris when she found her mentor in the person of Antoine Bourdelle, who integrated her into his studio (1926-1929) and substantially contributed to her ambition to become an artist. After her years of training, in 1930 Germaine Richier opened her own studio in the Montparnasse district. Her early works quickly gained notoriety and attracted students. In 1939, the year war was declared, she moved to Switzerland where she moved away from the ‘illusionist tradition’ towards a more singular style. After exhibiting in Basel, Bern and then Zurich, she returned to her Paris studio in 1946. She then resumed her work as a teacher and continued to create hybrid figures.

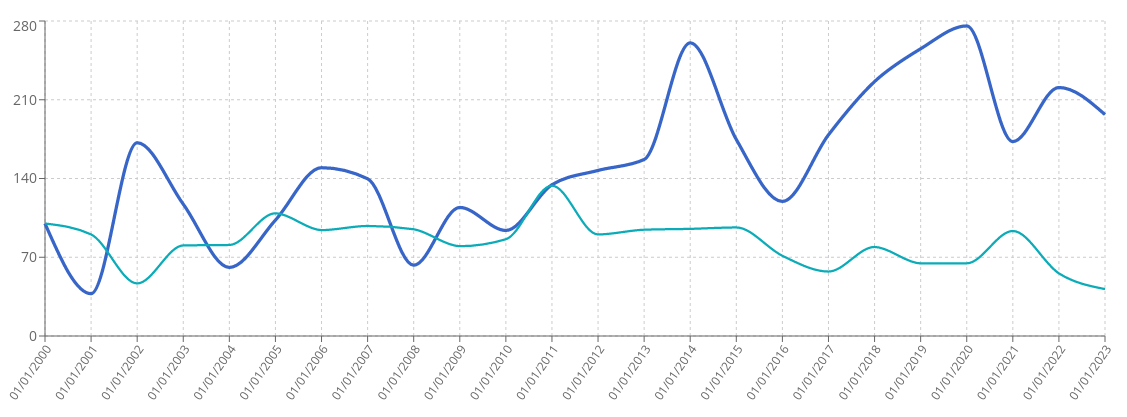

Today, Germaine Richier’s market prices are higher than her teacher’s. Émile Antoine BOURDELLE, considered the greatest living French artist of his time after Rodin’s death, has an auction record at $1.4 million (for Héraclès archer, 1909), whereas Richier’s top result is more than double that price at $3.6 million for Bullfighting (La tauromachie, 1953). The comparative auction price indices of Germaine Richier and her mentor Antoine Bourdelle show that Richier has a much more interesting price dynamic.

Relative auction price indices of Germaine Richier and Antoine Bourdelle (light blue). (Copyright Artprice.com)

A generous and singular work

Richier worked from live models. Her initial recognition and successes were based on her portraits and nudes. When WWII started, she forged new images of the human figure hybridized with animal and plant forms. Her forms were inspired by her fascination for all living things… the roots of trees, insects, etc. She merged animal and plant kingdoms, inventing creatures with long limbs, creating a phantasmagorical world, working sculptural masses from within. Her gestures clearly involved scratching, digging out, excavating, bending, stretching, twisting, giving organic form to matter, creating new and changing forms of living creatures. As someone who loved life and who loved everything that moved, Richier reveled in the potential expressiveness of surfaces, hoping to give the impression that her sculptures will actually move.

“I love life, I love what moves, but I don’t try to reproduce movements, I try to suggest them. My statues should give the impression that they are still and that they are going to move at the same time”. Germaine Richier

In 1945, her ‘natural’ forms took on a new grammar when she incorporated tree branches and leaves. This connected – both concretely and symbolically – all things human to the forces of nature in an imaginary world steeped in archaic myths, nourished by legends of origins. Indeed, one could say there is a fundamental and unique magical element in Richier’s sculptures.

Fascinated by materials, shapes, surface qualities and collected objects, Richier constantly experimented, working with earth, plaster, bronze and, after 1952, with lead into which she inserted pieces of colored glass to bring her sculptures even more to life and add joy to her creations. Her propensity for experimentation and her extraordinary capacity to bend and extend classical conceptions of sculpture earned her the admiration of many great artists of his time, including Pablo Picasso and Max Ernst. Even today, she is often described as “the female Giacometti”, a way of emphasizing the originality of her work by comparing her to the most famous (and expensive) sculptor in art market history (the only sculptor to have created three works that have fetched prices above the $100 million threshold).

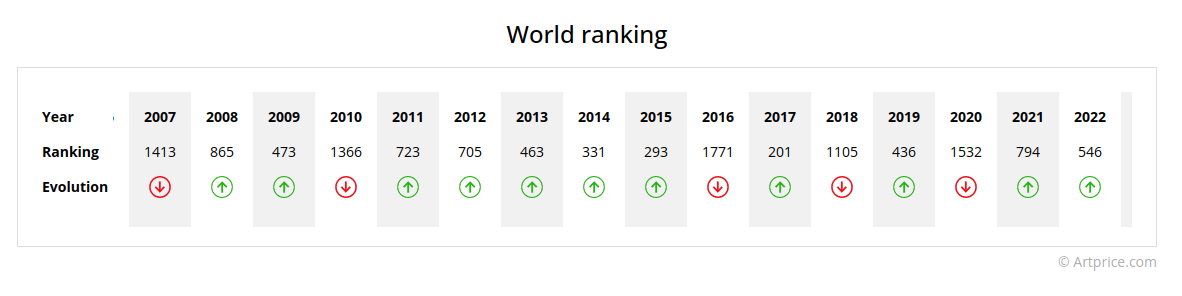

Germaine Richier’s position in our global ranking of artists by annual auction turnover (Copyright Artprice.com)

Recognition… and prices

The recognition of female artists has always been less forthcoming than for male artists, and even less so for female sculptors (vs. painters). However, despite a relatively short artistic career (between 1933 and 1957), Germaine Richier seems to be an exception. She was admired by the great artists of her time and benefited from numerous exhibitions – especially in museums – during her lifetime, and those exhibitions had a similar resonance to those of her male counterparts in the world of sculpture.

In 1936, her first solo show at the Parisian gallery of Max Kaganovitch was much noticed by the artists and writers of her time. The following year, she received the Medal of Honor for Mediterranean at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, and in 1939 she participated in New York’s World Fair. In 1948, the Maeght gallery organized a major exhibition of her work in Paris and devoted an issue of the magazine Derrière le miroir (Behind the Mirror) to her work.

In the 1950s, her work was widely shown abroad: her L’Orage (1947-1948) was presented at the Venice Biennale in 1950, and in 1951 she won the first prize for sculpture at the first São Paulo Biennial. In 1952 she returned to the Venice Biennale, and in 1953 she returned to the São Paulo Biennial. So, already in the 1950’s, Richier’s singular work enjoyed very substantial international recognition.

Richier’s first retrospective at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris took place in 1956. She was the first sculptress to be exhibited there. The MoMA showed her work several times in the 1950s: in 1955 as part of the exhibition The New Decade: 22 European Painters and Sculptors, then in 1959, shortly after her death, in an exhibition titled New Images of Man, where her sculptures were exhibited alongside works by Giacometti as well as paintings by Dubuffet, Pollock and Bacon. In total, the MoMA has included works by Richier in around ten exhibitions.

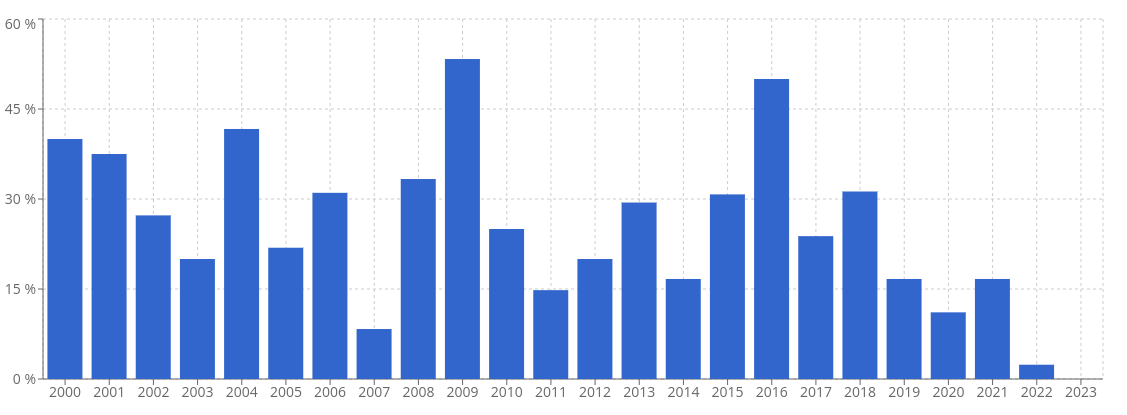

At a time when the art market and museums are making a conscious effort to reduce the gap between male and female artists, Germaine Richier is enjoying a well-deserved spotlight involving a proliferation of publications and exhibitions over the past decade. Indeed, all her works that have fetched over a million dollars (there have been 10 at auction) have been hammered during the last decade and we note a clear increase in demand over the last three or four years: her unsold rates are particularly low, both for her sculpted works and for her prints. Her highest sold-through rate was recorded last year at a remarkable 97.6% and it is just possible that this peak in demand had something to do with the Pompidou Center having scheduled a major retrospective of her work…

Germaine Richier’s unsold rate at auction: lowest in 2022 (Copyright Artprice.com)

Germaine Richier Retrospective:

The exhibition at the Pompidou Center in Paris started at the beginning of March and will continue until 12 June. It will then be transferred to the Fabre Museum in Montpellier, from 12 July to 5 November 2023.

.

30.6

30.6