Ernest Pignon Ernest: an engaged and modest pioneer

[03/01/2023]Despite being considered a pioneer of Street Art, Ernest Pignon Ernest’s work is less popular than that of many young artists in vogue. We take a look at his unorthodox artistic career and the still affordable market for his work.

At eighty years old, freshly elected to the Academy of Fine Arts (2021), Ernest Pignon Ernest does not see himself as being part of the Street Art movement. Indeed, his intentions, his style and his aesthetics are quite different from those usually associated with Street Art. Nevertheless, for over fifty years now, Monsieur Pignon-Ernest has been creating art in the street with a poetry and a constancy that has elicited admiration from the most popular and highly rated urban artists… including Banksy.

Off the beaten track

Ernest PIGNON-ERNEST was born in the southern French city of Nice in 1942 to a hairdresser mother and a father who worked in abattoirs. Nothing in his family context predestined him to art, but he showed a gift for drawing from early childhood. After obtaining his ‘National Diploma’ in 1957, he worked part-time with an architect, which allowed him to earn a living while perfecting his drawing technique.

In the effervescent atmosphere of his hometown in the 1960s, the young man rubbed shoulders with artists like Ben Vautier, Arman, Claude Viallat, Martial Raysse and Bernar Venet. He was already passionately interested in both poetry and painting, inspired by El Greco, Picasso and Francis Bacon, who would later express his admiration to him. In 1966, he moved to the Vaucluse where he made his first installations in a public space: a black silhouette evoking the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at a time when France was using the nearby Albion plateau for certain nuclear installations. Already, he considered that “it is not a question of making political images, (but that) there is a political way of making images”. Henceforward, his drawing would always be poetic and socially and/or politically engaged: Ernest Pignon Ernest has always sought to raise awareness, drawing attention to episodes such as the Algerian War, Simone Veil’s courageous political battle for abortion rights in France, the struggle against Apartheid and then AIDS in South Africa, and the situation of migrants in Europe, among others.

Ernest Pignon Ernest’s drawing is academic, meticulous, and aesthetically demanding. Very marginal to contemporary art trends, his style has sometimes been described as anachronistic, and yet it is the realistic power of his life-size human figures that grabs your attention. Because each figure, screen-printed and then glued to an urban space, suggests a presence that inevitably elicits some kind of emotional response from passers-by. The spot chosen for the work is essential in this approach as the image is designed to fit into a specific place that the artist tries to understand beforehand, not just materially, but also historically and symbolically.

How has the art world responded to his work?

Before being screen-printed, the images are initially large drawings patiently made in the studio with charcoal, erasers and white paint. Nothing in common with the urgency of the ultra-colorful graffiti that usually adorns our urban landscapes. But as he was one of the first to take art to the streets in the 1960s – pasting his images at night and doing so ‘without permission’ – Ernest Pignon Ernest is considered a pioneer. Street art is therefore an unclaimed label that has earned him increasing popularity in recent years.

Taking art to the streets means offering it to the widest possible audience. Some drawings have gained immense popularity: Pasolini holding his own body in his arms and the portrait of Rimbaud stuck on the walls of many cities since 1978 have become iconic. Although adored by the general public, admired by many artists and thinkers and represented by a historic and international gallery (the Lelong Gallery) since 2009, Ernest Pignon Ernest has received only scant support from cultural institutions. In 1979 his work was exhibited at the Animation Recherche Confrontation (ARC) of the Museum of Modern Art of the city of Paris, at the invitation of Suzanne Pagé; in 1986, he was present at the Venice Biennale at the invitation of Italy; then in 1995 at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in his hometown, Nice. But as a general rule, the major exhibitions in which he has participated (Munich, Beijing, Geneva, Rome, etc.) are the fruit of foreign or private initiatives. This is the case of the largest retrospective of the artist’s work to date, organized in 2010 by Bénédicte Lesueur and Henri Jobbé-Duval in La Rochelle (490 works), and again today, with the major exhibition of his work in Landerneau, at the Hélène & Édouard Leclerc Fund for Culture (until January 15, 2023).

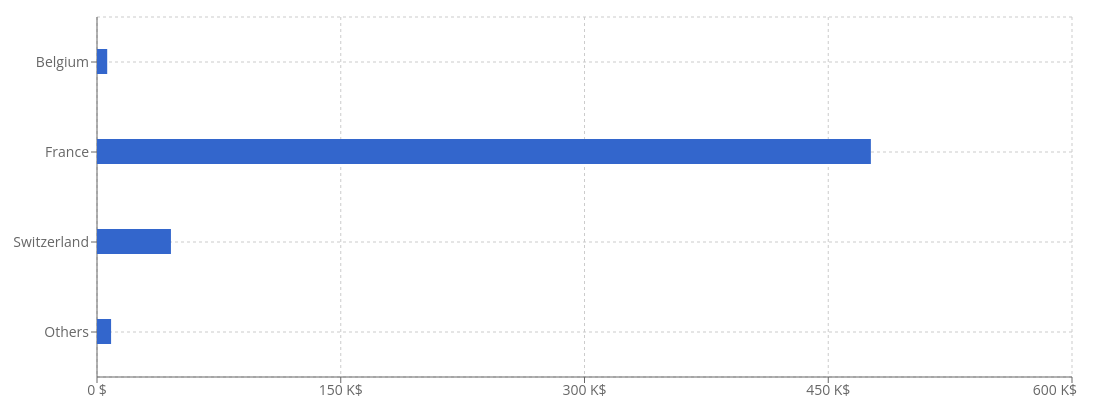

Ernest Pignon Ernest: turnover at auction by country since 2000 (copyright Artprice.com)

Rare drawings in demand

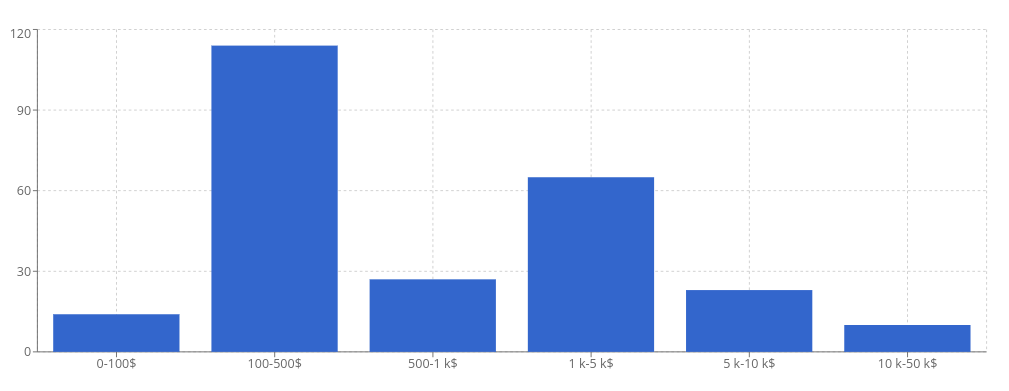

Fragile and ephemeral, Pignon-Ernest’s street works are destined to disappear sooner or later; but the artist keeps all his sketches, preparatory works and of course photographs. The works produced before and after the installations are marketed, as well as prints, which constitute approximately three-quarters of the works sold at auction (73% since 2021), mostly sold for less than $500.

Ernest Pignon Ernest : distribution by price segment since 2000 (copyright Artprice.com)

Ernest Pignon-Ernest is therefore a decidedly affordable artist, including for his unique works whose prices have not yet caught up with his notoriety. The best drawings – large formats measuring over a meter (sometimes two meters) – sell for between $15,000 and $25,000, while his more modest formats, or mixed techniques combining drawing and photography, can be acquired for around $10,000. However, his prices at last appear to be inflating as drawings recently offered at auction have been particularly hotly contested. Estimated at $1,500 last May at Geneva auctions, a study in Indian ink, executed in 1997 for the series of characters installed in telephone booths in Lyon and Paris, fetched $8,880 (Composition n°57 (cabine téléphonique)). This was a substantial price for a drawing measuring just 24 centimeters… Was the enthusiasm related to the fine quality of this small format work, or was it a clear sign of price escalation? His drawings are too rare (generally no more than five sold at auction per year) and his collectors too determined not to conclude the latter.

30.6

30.6