Focus on Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

[12/05/2020]Lynette YIADOM-BOAKYE (1977) creates portraits, but rather than posed portraits they are imaginary portraits which she usually tries to finish in a single day. As a result, her paintings express a high level of intensity, created with short and expressive brush strokes. Her palette usually contains dark tones, which lend a certain drama to her subjects, contrasted by a few flashes of light. Although the ‘portrait’ genre is an absolute classic of art history (that has been thoroughly explored ad infinitum), there is something about Yiadom-Boakye’ paintings that is profoundly new. Moreover, by placing her black subjects in the midst of Western art historical codes (the pose attributed to the figures, the somewhat classical compositions, the anachronistic clothing…), her paintings open several cultural windows at the same time and introduce an exhilarating element of confusion into our perception.

To grasp the full significance of the pictorial-parody element of Yiadom-Boakye’s painting you have to see it through the prism of British art history. Back in the 1980s a number of black artists explored identity issues, and the work of British Black Arts movement and Black Women Artists community contributed important chapters to the spectrum of artistic creation at the time. English artists from African diasporas have therefore been tackling issues relating to Britain’s colonial past and the artistic representation of black people for nearly forty years. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s work appears to be a continuation of the same movement. Considered an essential contribution to the revival of black figure painting, her work has been integrated into the permanent collections of important museums in London, such as the Tate.

A golden opportunity at the Tate (20 May to 31 August 2020)

By offering Lynette Yiadom-Boakye her first major retrospective, London’s Tate Gallery (currently closed) has opened a golden gate for the British artist while pursuing one of its key strategic orientations, that of tracing the history of British art without omitting artists from diasporas. Ten years ago, a first exhibition at the Tate traced the impact of black artists and intellectuals on early 20th century modernism (as it relates to art) through to the present day. Under the title Afro Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic, the exhibition focused on visual and cultural hybridity in Modern and Contemporary art, and brought together artists like Picasso, Kara Walker, Isaac Julien, Adrian Piper, Ellen Gallagher and Chris Ofili. In 2011, the institution invited Lubaina Himid, a figurehead of the British Black Arts movement, whose work on the invisibility of the African diaspora earned her an OBE for services rendered to the cause of black artists. Two years later, in 2013, the Tate acquired a very political work by Eddie Chambers (entitled Destruction of the National Front). Known for his work on the duality between British identity and being black, Eddie Chambers has played a fundamental role in rewriting England’s artistic and intellectual landscape. His book Black Artists in British Art: A History Since the 1950s (published in 2014 and re-published in 2015) puts black artists back into the history of British art and cites Lynette Yiadom-Boakye among the recently acclaimed artists. Shortly before the publication of the book, the Yiadom-Boakyen was shortlisted for the Turner Prize alongside the artists Laure Prouvost, David Shrigley and Tino Sehgal and her work was exhibited at one of the most prestigious events in the art world, the Venice Biennale.

Already fetching 7-digit results

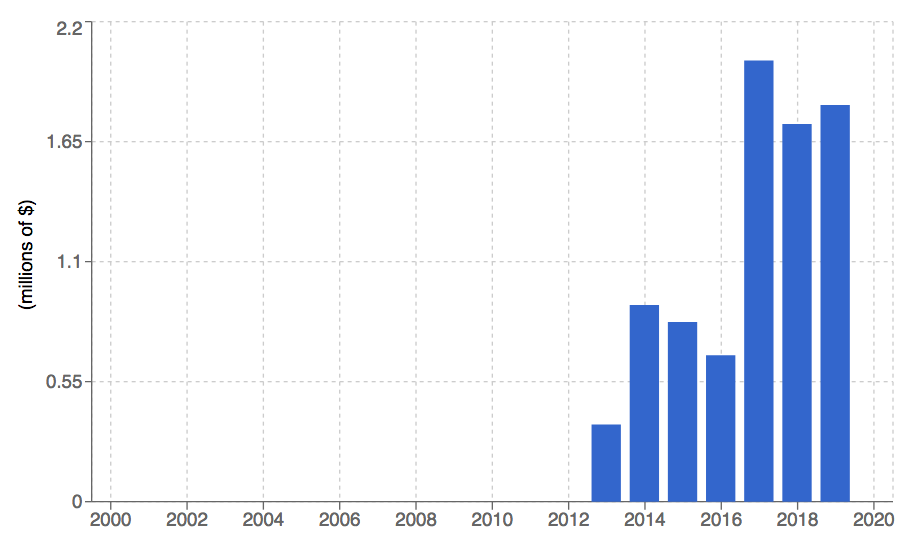

In 2013, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye had a sufficiently solid career foundation to test secondary market demand. At just 36, she already had substantial media exposure thanks to her Turner Prize shortlisting and her exhibition at the Venice Biennale the same year. In London, Christie’s and Sotheby’s both sold three of her works in the autumn of 2013 at what many would consider super-high prices for an emerging artist. On 17 October 2013, her canvas Politics fetched $84,000 and the following day Christie’s hammered $235,220 for a canvas carrying a high estimate of $80,000 (Diplomacy II).

In reaction to these successes, the auctioneers accelerated the pace and put 13 paintings up for auction in 2014, which the London market continued to absorb at good prices. But it was her integration into New York sales that really ignited her market. In 2017, Sotheby’s New York sold The Hours Behind You, a large canvas (250 cm) from 2011, for almost $1.6 million, i.e. four times its high estimate. So Lynette Yiadom-Boakye became a ‘million-dollar plus’ artist aged just 40.

After a quieter 2018, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye returned to art news in force last year when nine of her works were presented at the first Ghanaian pavilion at the 2019 Venice International Biennale and were widely acclaimed. Meanwhile, back in London, Phillips hammered another million-dollar result for her canvas Leave A Brick Under The Maple, exceeding the high estimate by $430,000 (27 June 2019).

The young artist was among the first surprised by the enthusiasm. But the surge in her prices seems to correspond to a certain type of painting that arrived at exactly the right time. Firstly, female artists are being consciously projected into the limelight for the first time in art history (and art market history) and secondly, the art world seems to have developed a new-found taste for works that question notions of nationality, nationalism, borders and which deliberately promote the crossing of borders (or all kinds). Ironically, these themes all seem to have acquired an even stronger, if somewhat altered, resonance with the coronavirus crisis…

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Chronological Progression at auction

0

0